Met de groeiende aandacht voor de hersenen in de wetenschap en de samenleving wordt het idee van ‘aan jezelf werken’ steeds vaker vertaald als ‘werken aan je brein’ (Dehue 2014; Rose & Abi-Rached 2013)813. Problemen die voorheen voornamelijk werden gezien als mentaal, zoals hyperactiviteit, obsessies of depressies, worden momenteel voornamelijk als hersenproblematiek aangeduid (idem).

Ook meer alledaagse problemen, zoals slaapproblemen, moeheid of concentratieproblemen worden steeds vaker in de hersenen gezocht. En voor mensen zonder specifieke problemen zijn er ook allerhande producten te verkrijgen, speciaal aangeprezen ter stimulatie van het brein, zoals pillen (smart pillen, nootropics), boeken (bijv. Het maakbare brein; Sitskoorn, 2006)14, voeding (brainfood), games (sudoku) of speelgoed (Ikea verkoopt bijvoorbeeld een hobbeleland die de hersenen helpt indrukken in het hoofd te sorteren).

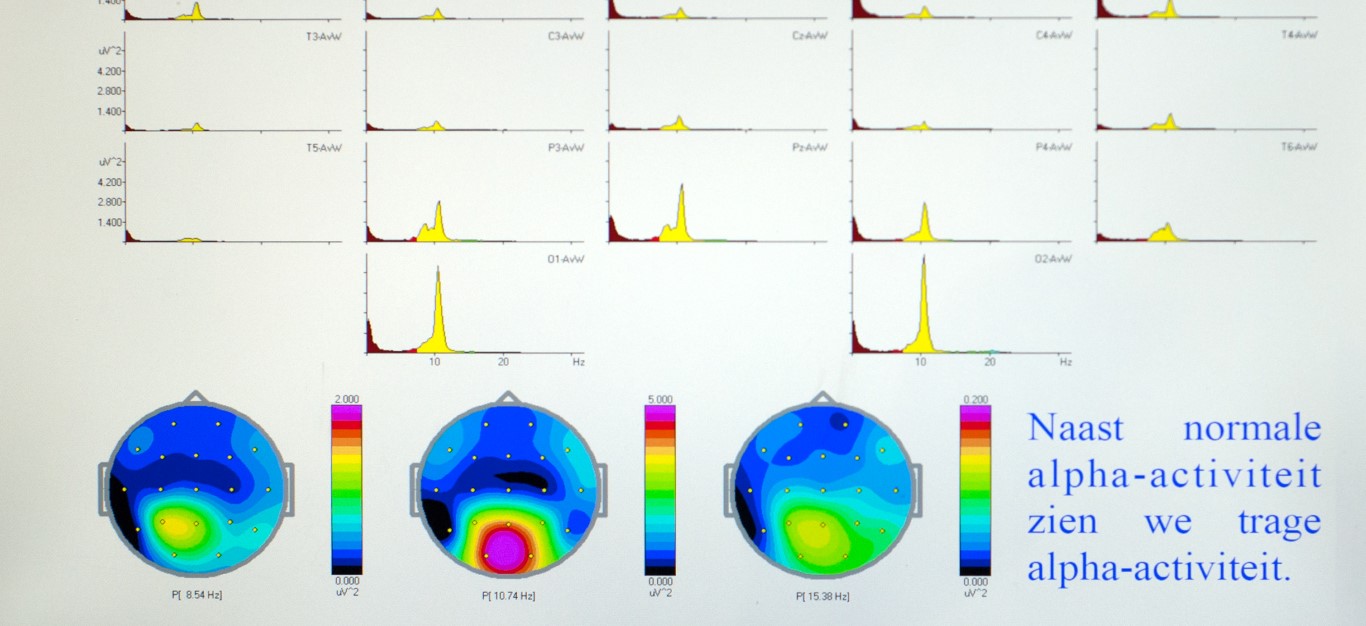

Daarnaast worden er via internet of speciale ‘hersenklinieken’ diverse apparaten aangeboden om de hersenen te stimuleren, zoals licht en geluidsmachines, elektrische of magnetische hersenstimulatie, en neurofeedback. Deze technieken zouden mensen kunnen behandelen voor ‘hersenaandoeningen’