Theory of mind

Hoe kan het lezen van literatuur leiden tot een groter inlevingsvermogen in het dagelijks leven? Een technische term voor inlevingsvermogen is Theory of Mind (ToM). ToM is de vaardigheid om een mentale staat, intenties, kennis en verwachtingen toe te kennen aan jezelf en anderen, en je ook in mentale gesteldheden van anderen te verplaatsen (Wellman, Cross & Watson, 2001)22. ToM omvat cognitieve en affectieve componenten (Shamay-Tsoory & Aharon-Peretz, 2007)18. Bij cognitieve ToM kunnen mensen overtuigingen en intenties van anderen interpreteren, terwijl mensen zich bij affectieve ToM een mentaal beeld kunnen vormen van emoties van anderen. Affectieve ToM is gerelateerd aan empathie. Maar anders dan empathie gaat het bij affectieve ToM om de cognitieve representatie van de emotie van een ander en niet om het opwekken van de emotie zelf (ShamayTsoory & Aharon-Peretz, 2007).

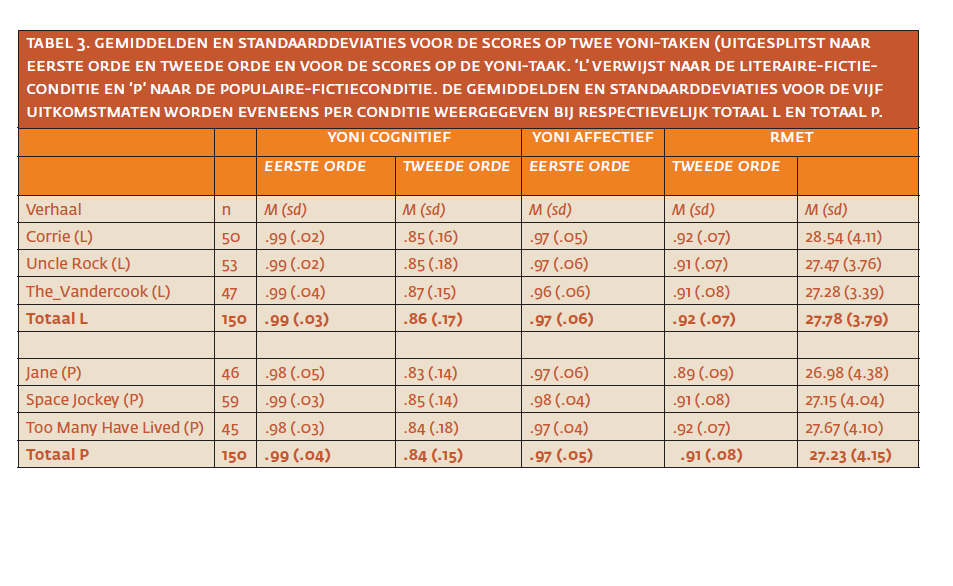

Deze twee aspecten van ToM zijn belangrijk; beide spelen een rol in zowel de persoonlijke ontwikkeling van